You may have read many resources on “Managing Up”, but you’re still unsure how to begin or if you’re doing it correctly. If you are like me, you may even dismiss it as jargon nobody cares about. But I have since realized that it can be transformative.

An excellent way to think about this is to invert the issue at hand. When you have a poor relationship with your manager, you probably talk less to each other. This means you get little advice on your personal development and career growth and little information about what is going on across the company. This significantly decreases your chances of influencing your company. Now, let’s flip this. By maintaining a good relationship with your manager, you are privy to valuable information, get the resources and advice you need to excel, and have an influence.

In the piece What holds people back, Shane Parrish says:

When we think of improving our value to an organization, we often think about the skills we need to develop, the jobs we should take, or the growing responsibility we have. In so doing, we miss the most obvious method of all: reducing friction.

He gives this example. If John and Jane have a boss who spends more energy trying to get John to do something than Jane, it’s obvious who will get ahead and who will be let go when it’s time to cut one of them.

Let’s take this idea a step further. Managing up is much more than reducing friction. It’s about creating a symbiotic relationship with your manager so that you both can succeed in your roles.

Maintaining a great relationship with your manager is easier said than done. They are trying to be your coach and evaluator simultaneously, making it hard to tell which role they are playing when talking to you. Every manager is different and brings different baggage with them.

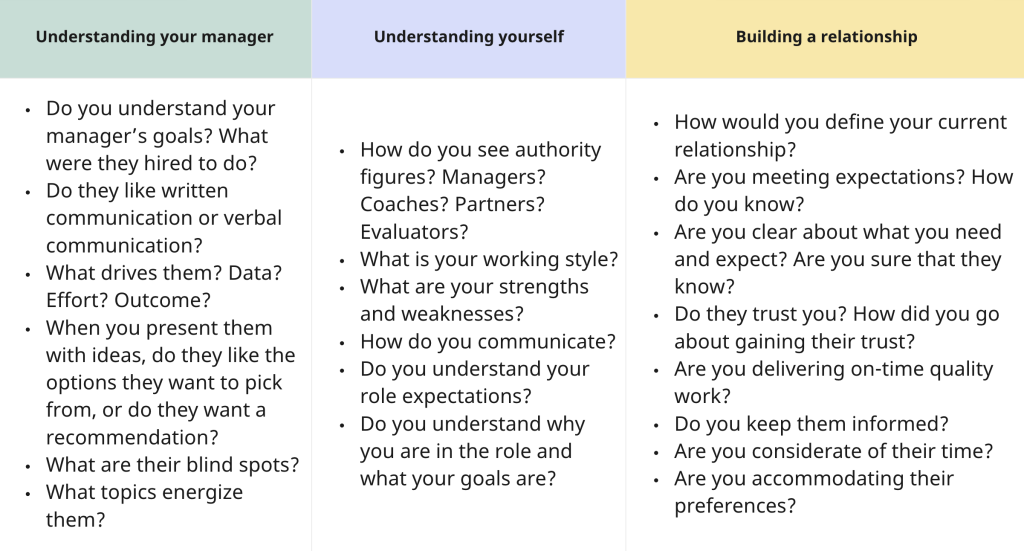

Your relationship with your manager is one of mutual dependence. You need your manager to succeed in your role, and they depend on your commitment to succeed. Your manager is human, too (some have argued otherwise!) – they have aspirations, frustrations, strengths, weaknesses, and fears, just like you. Consider these questions carefully. Source: Managing your boss

Scenarios

I have pulled some of these scenarios from Design Patterns for Managing Up (some parts verbatim) and have added a couple of my own. It’s important to remember that the scenarios are just a starting point and should be adapted to each unique situation. By considering the potential outcomes of each scenario, you can develop a plan tailored to the problem and help you achieve the best result.

Staying on the same page with your manager (literally)

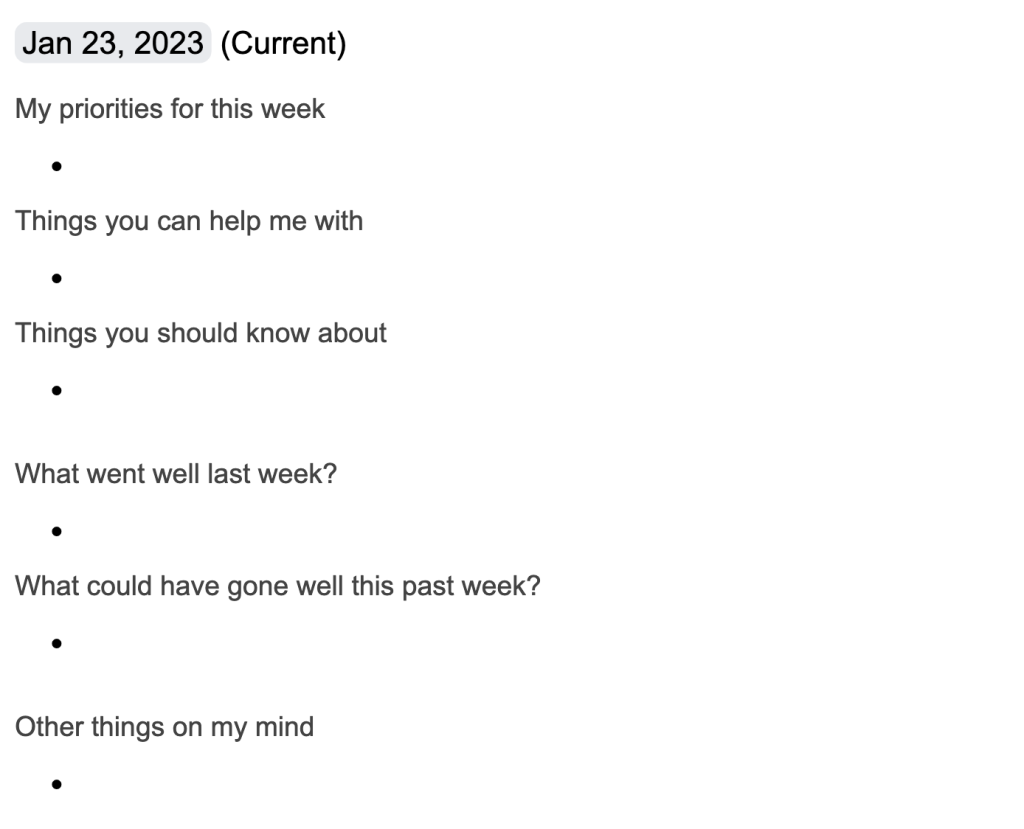

The most common way to keep in touch with your manager is through 1:1s. These meetings cover various topics, such as updates on key projects, feedback, coaching, and support. However, some topics can be forgotten or not discussed.

Will Larson takes the idea of “Do not surprise your manager” a step further in this post, adding “Do not let your sponsor surprise you” and “Feed your manager’s context.” One way to do this is the 15-5 document. The idea is that this document takes 15 minutes to write and 5 minutes to read and should be shared with your manager weekly. I have slightly modified Lenny’s “State of Me” format (Twitter post).

An SVP asks you a question, and you do not know the answer

It can be challenging to admit it when you’re put in situations where you don’t know the answer. However, a senior individual usually asks questions out of genuine curiosity, not to test you. Here’s what you should do instead:

- Admit you aren’t certain

- Take ownership of finding the answer

- Give a timeline for when you’ll follow up

- Provide a correct, concise, and thoughtful response

You think you are ready for a promotion

I used to think it was my job to do the work well and my manager’s job to get me promoted. However, promotions at big tech companies take a lot of effort. Typically, a case must be presented to a committee of other engineering managers and directors (sometimes VPs for Staff+ roles). The case must include a lot of evidence. While most managers have a good idea of your significant contributions to major projects, they may need to be made aware of your day-to-day contributions. Managers will need your help gathering this evidence and will put in as much effort as you do in your promotion.

Promotions at senior levels (Senior Engineer, Staff+ Engineer) can take several quarters, halves, or even years. Avoid the expectation of instantaneous results. If someone pushes to get promoted quickly, it is often a sign of not understanding the expectations clearly.

Go to your manager well-prepared to have a deeper conversation. Write a document that contains all of your significant contributions. Some things to think about:

- What projects did you work on? What was your role? What was the impact? Why was it complex? What documents do you have?

- What did you do outside your immediate role expectations to improve the organization?

- Have you mentored others?

- Who can advocate for you?

You get negative feedback from your manager

Negative feedback can be challenging to receive. However, it is also difficult for your manager to give it. No one enjoys conveying bad news; some managers may even admit it before giving it. But, handling it the right way can create a positive encounter with your manager and be an opportunity to grow.

When receiving negative feedback, it’s essential to remain calm. Focus on slowing down your breathing, be aware of your heart rate, and keep your face relaxed. Then, say, “I hear you. I will be more mindful of that in the future.”

If you would like more information to understand their perception or suggestions on how you can do better, ask. If you are calm at the moment, ask them immediately. If not, stop with those words, walk away, and follow up later.

There is a decision made that you disagree with

At work, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. It is not necessary to always agree with leadership decisions, but making the company as successful as possible is essential.

It is essential to take emotion out of the equation and wait a day or two to clear your head if needed. Instead of immediately disagreeing, ask about the context and reasons for the change. If you have a prior relationship with the primary decision maker, start with them. If not, start with your manager and escalate through the chain of command. Research and present alternative options that will achieve the same goals. If you cannot sway the decision maker, support the action plan. Be sure to share the context and reasoning with your team, and then do everything you can to improve the situation, such as helping the cause succeed or mitigating any fallout.

There is a problem that is your fault or responsibility

Funnily enough, this looks like incident management!

Let key people know and establish yourself as the owner. Share the next steps if you know them. If you don’t know, share a time by which you can provide an update. Be as specific as possible. Communicate known unknowns. Give a timeline, what solutions you will try and when to expect results.

You notice a problem or opportunity that is NOT your responsibility

There will be many problems that you encounter in your daily work. Having a shared understanding of your role expectations can help you understand your responsibility and what isn’t. Many workplaces expect you to have a “Bias for Action,” encouraging you to have a sense of ownership in your work; if you notice a problem, you should take ownership of it until you find someone better suited to handle it.

When dealing with a problem, there are a few things to keep in mind:

- If you are working on something more substantial, take note of the problem and don’t let it distract you. Let your manager know that a problem exists, but you have more important tasks to focus on now.

- When you are ready to tackle the problem, communicate with your manager in their preferred style (mine is generally a document). Describe the issue, identify a solution or approach (with multiple solutions considered), and consider any second-order effects.

- Finally, take ownership of the outcome.

Now that we have discussed some principles of managing up and how to apply them in everyday work situations, consider how you would manage up in the following cases:

- Your peer is not contributing their fair share

- You wish to switch teams

Don’t suck up! Manage up!